Tales Trees Tell

On August 15 I had a chance to speak at the Canadian Association of Geographers conference in St. John’s as an invited speaker on a session around research and storytelling. I spoke about the development of two radio documentaries and how some of those concepts can be applied to a research process. The two documentaries were The Invasions and The Grand Old Willow Tree. Both of these documentaries were developed for CBC’s Atlantic Voice program.

Press Play to hear The Invasions:

Press Play to hear The Grand Old Willow Tree:

These are the speaking notes for the presentation:

1. Good morning. My name is Bojan Fürst and I do work here at Memorial and I even hold a graduate degree in geography, but that’s not why I am here today. Today, I am going to talk to you as a radio documentary maker and photographer who loves working on science-y kind of stories. Thank you Carissa for inviting me. This is the first time that I actually get to speak about my radio documentary practice. And so this is not going to be a very academic presentation, but I do hope that there is enough here to help you think about your research a little bit differently. Let’s dive right in.

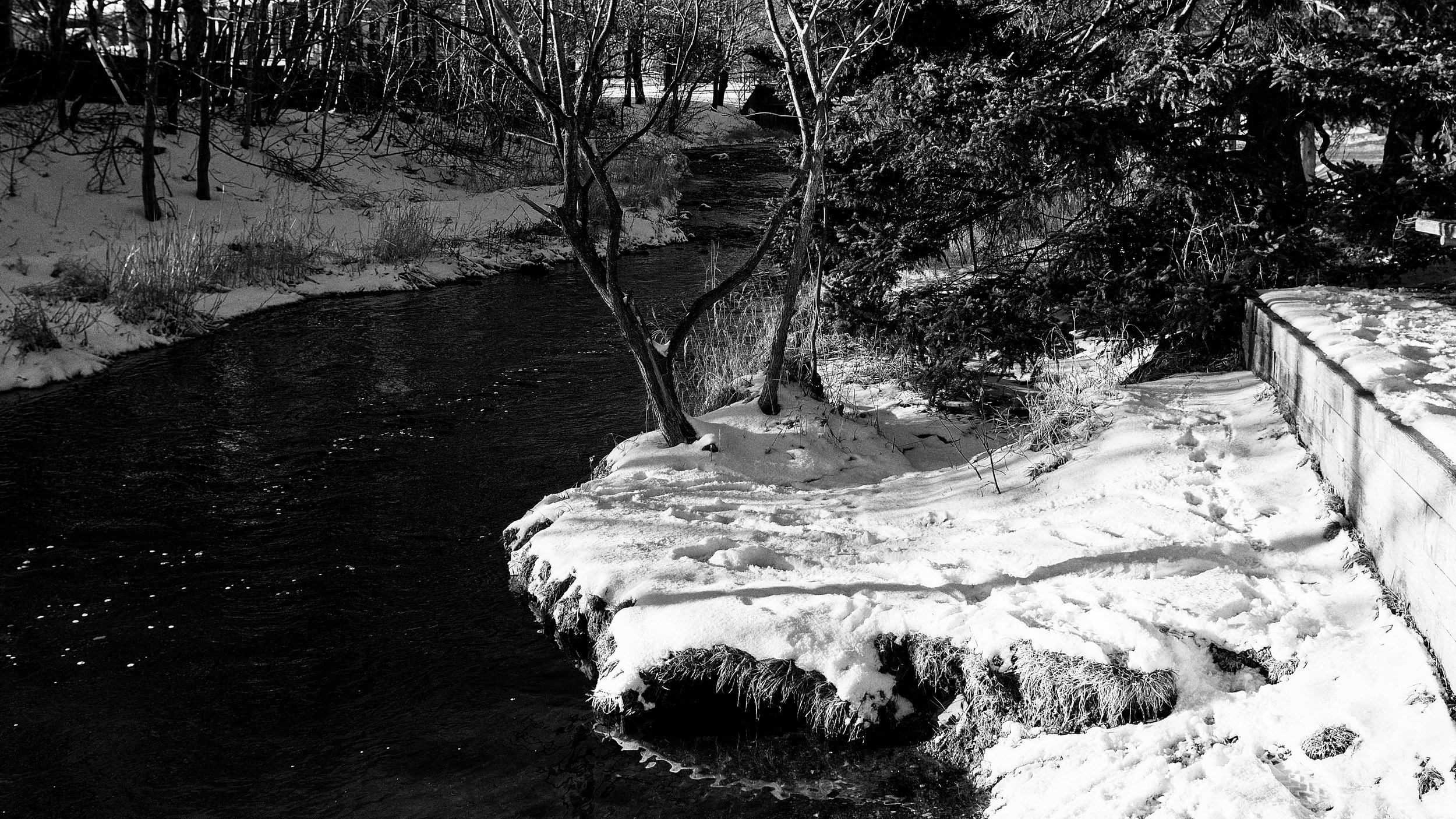

2. The two documentaries I am going to tell you about started as a single photography project at the beginning of the pandemic. Here on the island of Newfoundland, we were luckier than folks in many other places and the relatively low prevalence of the cases at the time and our public health measures still allowed us, with some basic precautions, to go for a walk. And walk I did! Every day, for almost three years, I walked along Rennie’s River and made photographs - lots of them.

3. Rennie’s River is a small urban river that connects Long Pond, here on campus, and Quidi Vidi Lake about three kilometres east from here. There are really beautiful walking trails along both ponds and all along the river as it flows through some of the older and relatively wealthy residential neighbourhoods.

4. We can’t listen to the radio docs because each is half an hour long. So the best thing I could do is create a page on my website with this presentation and the audio for both of those docs and the links to the transcripts. I will have the link on the last slide here. The first documentary was called The Invasions and it featured a virologist, a horticulturalist, a historian, a biogeographer and a veterinarian. The second one was called The Grand Old Willow Tree and it featured a biogeographer, an urban forester, an artist and a lawyer (sort of). Both of them, also featured the river and many, many trees and plants.

5. There are two concepts that made these two documentaries possible and I think they translate nicely into a research practice as well. The first one comes from the British anthropologist Dawn Mannay. She urges researchers to use a range of techniques to defamiliarize themselves and their participants with their subject matter - in her words “to make the familiar strange.”

6. Mannay argues that using creative research or artistic research methods can help us explore previously taken for granted understanding of the world around us. She mostly considered this as a research technique to help participants engage with the every day, but it is just as powerful if you use it to break your own habitual way of thinking about or looking at something.

7. The second concept I want to talk briefly about comes from John Berger - a writer and a visual theorist - mostly of photography. Berger spent a lot of time thinking about photographs and time. One of his insights is that photographs - you can think of them as fragments of knowledge like an interview or a data set - need to be contextualized in order to again become part of a larger web of knowledge and history.

8. Berger suggests that the way to go about it is to build that context with words, other photographs or anything really that helps us reconstruct what he called narrated time - a complex story that is embedded in memory and historic time giving us a sense of continuity and allowing us to imagine a future.

9. Here is how I used those two concepts to build the documentaries and I think this maybe a useful way to think about the broader story our research sits within. The first documentary, The Invasions, started with my annoyance at endless zoom meetings and the way work invaded my home as a result of the viral disease we were trying to prevent from spreading. I photographed along the river because that was pretty much all I could do, but when I started looking at those photographs I realized how little I knew about the river I walked along several times a week for past 10 years on my way to work. The photographs helped me turn this familiar landscape into something unfamiliar - or strange. I could not name most of the trees and almost none of the plants. I knew nothing of the historic context of the river and how it shaped the city we are in and how we shaped it in turn.

10. I wanted to understand the COVID-19 virus better so I talked to a virologist. I downloaded a plant identifying app and found out that most of the plants along the river are considered invasive species. So I talked to a horticulturalist at the Botanical Garden. And of course, the trees. Some of them familiar to my Central European eyes but growing and behaving differently and Carissa provided stories and explanations to the questions I had. I started reading the historic plaques along the trail and found out that Cluny McPherson, the inventor of an early gas-mask during the First World War lived nearby so I talked to a war historian, dug in the archives to find an audio recording of the gas shells fired on the front. And the COVID virus is a zoonotic virus so I talked to a veterinarian to better understand the connection between the climate change and habitat loss and the spread of diseases.

11. There were suddenly so many unanswered questions. The chief among them was about the fate of the grand old willow tree. Rumour had it the city was going to cut her down. That sounded like a whole other story. And so Carissa and I stood under its generous canopy one day and she span stories about willows and urban trees and fungi networks and the struggles all these European species went through to cope with Newfoundland’s terrible soil and even worse weather.

12. I talked to an urban forester who could list - alphabetically - all the services trees provide to us from storm water management to erosion prevention to making our cities livable and beautiful. I found paper from the 70s where a lawyer in California argued that we should acknowledge trees as persons and appoint guardians who could argue on their behalf in the court of law.

13. I also spoke to an artist who lives and works in Japan and Korea where a relationship with old trees is formalized in a way that blends spiritual significance, community spirit and aesthetics. We wondered what would a culturally appropriate equivalent look like in a place such as St. John’s. And there was even room for personal reflection spurred on by memories of trees that meant a lot to me.

14. We talked about poor urban planning decisions and inevitable consequences such as flooding further exacerbated by climate change. All this to say that finding a way to look at familiar things in new ways and building a context around those new insights was fun and immensely satisfying. It makes for better, more complex and messier, but more interesting stories that ring a little bit more true.

15. Obviously, you are researchers and not documentary makers and you need to maintain focus on the thing you are researching. But this kind of contextualizing and making the familiar strange practice doesn’t need to be onerous. Keep a research journal, make some photographs - it’s fine to do it with your phone - and look at them later. Sit for ten minutes by a river or a seashore or in a field or in the middle of a city for that matter and record the sounds around you. Listen to the recording and notice things you missed. Draw, however badly - it forces you to pay attention. Go talk to the people who might be able to help you see something you are familiar with from a different perspective. And even if all that information will never make it into an academic paper you write, it will help you see your work as a part of our collective striving for understanding of this place we live in. And that feels good.

16. As promised, here is the link to the website. If you click on the link there, you can listen to the documentaries, see all the photos from the Rennie’s River as well as find links to a couple of other related things. Thank you!

Also of interest maybe the essay connected with these documentaries: River Walks and Where Documentary Projects Come From.