🔊 The Grand Old Willow Tree

The Grand Old Willow Tree is a radio documentary that aired on CBC’s Atlantic Voice in December 2021. You can hear that original documentary wherever you get your podcast or by following this link or simply click on the play button below. The story below is more or less the direct transcript of the documentary.

“I see something kind of ancient and due for respect in St. John’s. This tree has been here for a long time and a lot longer than the folks who walk past it – maybe longer than all of the folks walking past it have been here.”

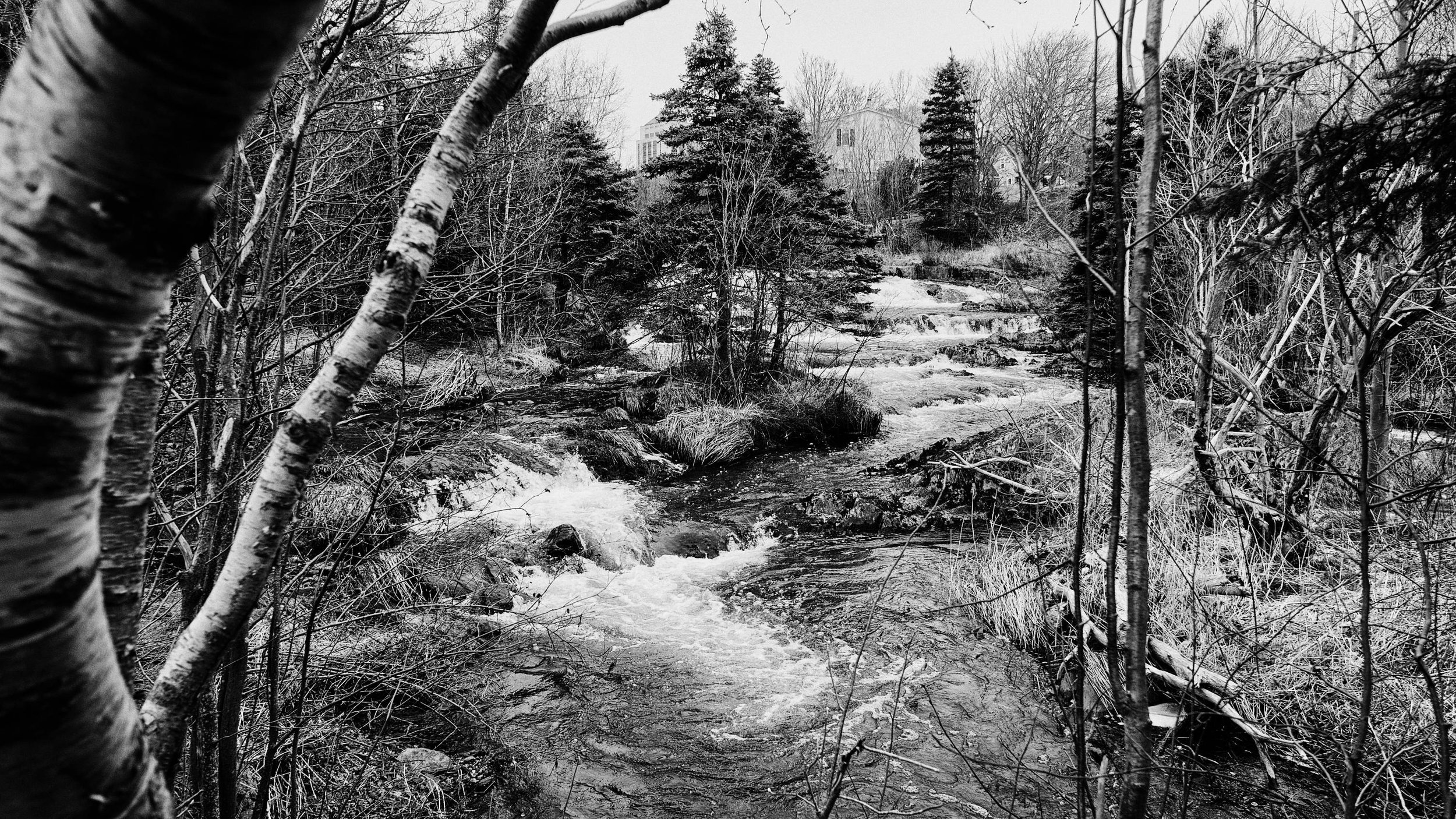

Dr. Carrisa Brown and I are standing under a large willow tree – so large that an entire lookout sits among its six or seven trunks, a small deck overlooking the Rennie’s River. There are rumors the city is planning to cut the old lady down. I emailed the city arborist hoping to clear those rumors up. In the meantime, here we are under her generous canopy.

Dr. Brown is a biogeographer at Memorial University who studies boreal forests. I make documentaries. The willow, she does a lot more and we are both very impressed.

“It has seen things, this willow tree. You can see where it has been damaged in some way and then there has been bark and wood building up in those damaged areas,” Dr. Brown said running her hand over one of the trunks. “The bark is one of the things that’s really appealing about it because you can see up the stem, there is moss growing in it. Because that bark is really thick it can hold a lot of moisture and then it becomes home to many other species. In that moss, there are little tiny invertebrates, there are insects living under the bark – all taking advantage of that habitat that the big giant tree, for Newfoundland standards this is a huge tree, is creating.”

The willow is truly impressive. She hangs over the river and the trail, luxuriously sprawling in the sun. It is impossible not to touch her as you pass by. The texture of the bark is irresistible.

It reminds me of another tree.

***

I grew up in the shade of a great horse chestnut in the town of Sisak, in Croatia. It grows in the yard of a 19th century, two-storey, brick apartment building built for railway workers. My grandfather was one of them. The train station and the tracks are just beyond a waist-high wall south of it. That tree was the seat of parliament for the neighbourhood six-year olds. We met there, plotted our adventures and heists (mostly of plums and cherries from the neighbourhood backyards).

On our last trip to the old country, when our daughters were old enough to remember things, one of the people I wanted them to meet was the old horse chestnut. If I am honest, I wanted the horse chestnut to meet them. I wanted the old tree to know that I turned out alright and that there are two new saplings out there in the world.

It really felt like I was introducing them to an old family patriarch. I even made a photograph of them under the chestnut - just like we made photographs with grandma and grandpa and great aunts and uncles. Because we are not alone in this world. Not even trees stand alone. Especially not old trees like my horse chestnut and the old willow on the Rennie's River bank.

“Well, no individual can exist in a completely solitary way so she has a huge network of roots underground that are connected to fungi that are sharing resources with the tree, and so the fungi will gain carbohydrates, like sugars from the tree, and in return, the fungi give the nutrients from the soil to the tree so they have this relationship with one another and there is nearly no tree on earth, possibly no tree on earth, that doesn’t have some sort of relationship with fungi and those fungi have networks spread all through the soil,” explained Dr. Brown. “You cannot dig a patch of soil and not find fungi. So perhaps this tree is not directly connected to that maple tree that’s just on the other side of the fence, but they are both part of this big underground web of life that’s filled with fungi, microbes, bacteria, all involved in transferring nutrients through the soil.”

That’s how things work in a forest. Trees connect to each other and not just trees of the same species either. They nurture the youngsters, take care of the sick and support the elders. In a city, things work differently.

Dr. Peter Duinker is a professor emeritus at Dalhousie University in Halifax where he taught in the environmental studies department. He said that the problem with urban trees is that we often plant them so far apart there is no possibility for roots and fungal networks to associate the trees. “The other part is that we often have infrastructure in the way and so the fungal networks and roots can extend under street pavement and sidewalks and so on, but the construction practices of the last decades have compacted the underneath surfaces, underneath the concrete and the asphalt, so hard that it becomes like an impervious pavement itself and so the trees do have a lot of difficulty in the newer roadscapes for example to be able to make the connections across trees,” he said.

Urban forests, all the trees and the soil they grow in and the plants and animals that grow around them, struggle. Often, they are also trying to put down roots in a place very far from their original home. Dr. Carris Brown has all the sympathy for the trees that were brought to Newfoundland from Great Britain and Europe. The climate alone was punishing for them. “I am sure that many trees over the years have not survived in Bowring park, in Bannerman park, but those that have are just so tough,” she said. “They can withstand so many different kinds of stresses and still look beautiful and persist and give so many services to folks that are able to enjoy those areas and so they are giving shade, they are providing entire habitats for just a suite of different species that live in them and use them. The shade on the ground means that there is cooler soil in the summer for underground species to use, they help with flooding mitigation. So the fact that there are trees all along the river here, while the river is pretty high, it means they’re helping to absorb some of that water, they are also helping – we just had solid 10 days of rain and all of the trees along these river banks helped to slow that water down instead of having it all rushing to the river at once and so they are providing incredible services and benefits to the city.”

Dr. Peter Duinker can easily rattle off a dozen of those services and benefits. He can even do it in an alphabetical order. He starts with beauty and goes all the way down to property values, shade, and storm water regulation.

I appreciate the old willow even more after talking to Dr. Duinker and I am starting to worry about what the reply to my email about her fate will be.

The nature of our cities is that they are not just built environments, but also social environments. Sure, geography, soil and climate matter to urban forests, but so do budgets, residents' preferences and a city's willingness to wade into dense politics of urban trees.

Dr. Duinker would much rather like us to think of cities as a forest with a few buildings and roads judiciously placed within. “I would call this social to the extent that it is kind of a cultural thing that we carry with us into the creation of cities,” he said.

Take an old city like St. John’s. This willow we are standing under is 150 or even 200 years old. It’s hard to tell. Dr. Brown and I wonder at the things it would have seen. Luckily for us, every tree keeps a detailed and accurate diary of everything they witness.

“On really good growth years, the rings are quite wide so if it is warm with lots of nutrients and just the right amount of moisture and lots of sun a willow might put a lot of wood in one growth year so we might have a wide ring. If it is a poor year, I keep hearing that the year 2008 there was no summer, well if we look back at the ring for 2008, it would probably be pretty narrow because it was cool, it was cloudy and so the tree likely did not put as much growth as it did in other years,” said Dr. Brown. She also explained that the tree cells can accumulate thing like lead and other environmental pollutants. “They have seen a lot of change in the city and this willow has seen an incredible amount of change in the city. I mean these trees that were planted earlier than the 1800s have seen the Great Fire of St. John’s. We might see a fire scar in some of the rings that were scorched in the fires, but then regenerated and so that is something that I really, particularly love about trees, thinking about all that they have witnessed through time. We use trees to tell us what has happened in a spot when we were not there to see it ourselves or when there is no record, written or oral record of what that area experienced through time and so they grow and persist and observe and absorb what’s happening around them and they record a record of that,” she said.

If our short lives could be recorded in rings, what would we read in them? In 1986 my rings would certainly record the Chernobyl disaster. Would we register major political upheavals? The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989? Would there be tight rings of the early 1990s during the Croatian War of Independence? Large, sprawling rings recording my delight at traveling to Canada in the mid 90s for the first time? Or a scar when I felt the connection to my childhood and home break for the first time?

***

When I was six years old, we moved to a different neighbourhood about 20 minutes walk away from my chestnut. This was a brand new apartment building next to a busy road connecting my hometown with the capital, Zagreb. Along both sides of the road, a row of straight, tall, stately black poplars provided shade and protection from the sun and the traffic. On one side of the road was a residential neighbourhood we lived in and on the other side were some corn fields, a tree nursery, railroad tracks and, eventually, a river.

I loved those poplars. The thing is – I had no idea how much I loved them until the day, sometime in my 20s, when I came home from Canada and they were gone. The corn fields, which we plundered as teenagers, the tree nursery, and the flood plain on the other side of the road were gone, too. The whole area was paved over and big box stores, gas stations, car dealerships and parking lots covered that entire stretch of land. The poplars, dozens of them, were all cut down to ensure that the newly erected billboards could be seen from the road. Walking from the train station to my parents' place, it felt like a punch in the gut to see them gone. It broke my heart, but it also, in a very real way, broke the connection I felt to a place I grew up in. This was not quite my home anymore.

The old willow along the Rennie’s River, my horse chestnut and the lost poplars are not amenities. They are not biomass, or wood, or a percentage of city canopy. The trees and us are connected in deeper ways. Here in the West, we are reluctant to talk about those connections openly. In other places in the world, there are forests and trees that are revered. In Japan, where American artist and writer Patrick Lydon spends much of his time, the concept of kami makes that connection explicit.

“The literal translation would be god with a small G, I guess, but it's basically the spirit that resides in some part of the natural world or represents some part of the natural world,” said Lydon. “I think it’s kind of like an acknowledgment of the fact that there is something alive in this world that is bigger than ourselves. It’s an acknowledgement of this concept so it allows us to kind of relate to these things, these parts of the natural world, a mountain or a tree or the ocean, water. It’s not restricted just to Korea and Japan. There are these kinds of traditions all over the world. The fact that that is the case, that independent of each other all these different cultures have realized something about old trees Gosh. That says something,” he said.

Just think about it for a moment. Early medieval Irish alphabet ogham had 19 characters – each based on a sacred tree starting with shoreline pine and ending with a blackthorn tree. Japanese developed the concept of shinrin-yoku or forest bathing and German has a word for that feeling of being alone in the woods - Waldeinsamkeit - of course German would have a word for it.

I told Patrick about my horse chestnut and he told me about the tree he would climb in his neighbourhood in California where he grew up. In the village in Korea where he lives now, old men and old women each had their own tree that they would sit under and talk. They tell him that when something is that much older than you, you naturally come to it to seek wisdom.

“I am sure that every kid who had a big old tree around them in their childhood, if you think back, most people have this kind of experience – and maybe then it’s a question like did we lose this sense? If we as kids had it, if these grandmas in the village have it, did we lose it? Can we rediscover it? I think we can, if we put effort into it,” he said.

We still love trees. In fact, from Vancouver to Deli, from Belgrade to Hanoi, citizens again and again turn out in force to protect old trees scheduled for removal. Trees still matter to us. Peter Duinker from Dalhousie University remembers the backyards of Vienna where he lived for some time in the 1980s. Those backyards were full of fruit trees- apples, pears, cherries, and walnuts.

Dr. Duinker would like to see fewer lawns and more trees in our cities. He is pragmatic about it, but underneath that pragmatism is a love of forests and recognition of just how dependent we are on them.

“The more trees we have in the city, of the right kinds and in the right places, the better off we will be coping with a hotter city environment through the 21st century,” he said. “We need to be careful to manage the urban forest so that it will be as resilient as we can possibly make it in the face of the changing climate, but we better have those trees in the city so that our own ability to enjoy city life is raised in the face of the changing climate.”

I appreciate Dr. Duinker’s practical approach to urban forests, but I can’t stop wondering if there is a way for us to regain that child-like awe in front of a large, old tree?

Artist Patrick Lydon wonders that, too.

“We made it strange,” he said. “We made it strange because we created these social rules that kind of ignore trees, ignore nature, ignore our innate human relationship with the biosphere and all of the living things in it. We cannot disconnect ourselves from the system, we really can’t. Scientifically, it’s not possible, yet we do it in our minds and we do it with our valuations systems which value certain things and then ignore the value of other things. You know, that is just a cultural thing that is learned and we taught ourselves to ignore certain values in this life and gosh, we really need those values right now if we are going to fight climate change and repair all of this ecological degradation, and destruction and pollution, gosh!, we need that.”

Patrick wants us to think of ourselves as ecological beings - not somehow apart from the world around us, but instead as fundamentally intertwined with it. I asked him how we could do that.

“It just means trying. It just means trying to know what I am in a more substantial way than statistical way. I mean we see ourselves in a statistical way. We see ourselves as numbers and measurements, right? So if we think we are more than this, and I think all of us know that we're more than this, then it’s worth it to try and see ourselves as ecological beings, as living beings that are connected to the living world,” he explains. “How realistic is it to say that all of the world can be neatly categorized and organized and measured and valued with a number system? I don’t think that’s totally realistic. And I am not saying science and math and these things are not useful because they are amazing tools for us to understand the world, but we should also realize that there are other ways that are complimentary to science and complimentary to mathematics and complimentary to our monetary evaluation system. There are ways that are complimentary to these things to see the world and we have to find the balance. And gosh, it doesn’t look like we have a very good balance lately.”

For a long time, we’ve been quite determined to see ourselves as somehow above the rest of the natural world we live in. In 1972, Christopher Stone, a Professor of Law at the University of Southern California, thought that we needed to be brought back to our senses. And if that meant putting us on trial, so be it. He proposed that trees should have legal rights and a standing within the court of law.

He pointed out that we already have legal guardianship for people who for whatever reason cannot manage their own affairs. And if we already can treat a corporation as a person, why on earth not another living being such as a tree. He imagined a tree guardian who would legally represent the interests of a tree and the rich web of life each tree sustains. He argued this would be one way to save us from ourselves.

“The problems we have to confront are increasingly the world-wide crises of global organism: not pollution of a stream, but pollution of the atmosphere and of the ocean. ...coexistence of man and his environment means that eachis going to have to compromise for the better of both. Now we are beginning to discover that pollution is a process that destroys wonderously subtle balances of life… This heightened awareness enlarges our sense of the danger to us. But it also enlarges our empathy. We are not only developing the scientific capacity, but we are cultivating the personal capacities within us to recognize more and more the ways in which nature is like us.”

Christopher Stone wrote those words in 1972. I am afraid he would be disappointed in how little progress we made in the past 50 years. Patrick Lydon, through his art and writing, is reconnecting his audiences to the natural world one leaf and tree at the time. And he wants the trees to have a say in how we build our cities.

“I think that provocation of what if we let the tree decide how to build a city, that came from, not just from my imagination, it came from the experience of living in places where that is the case in a small area so I guess the question is what if we expanded the realm of those special areas to take over more parts of the city and I think the answer is that we would have a really beautiful, sacred, slow, calm, peaceful, wise place that we live in that would than come back and help us understand how to live more peacefully with compassion for all beings, for our neighbours,” he said adding that we all want those kinds of peaceful places to live in. “In those small places where trees are respected, we have that. Those places already exist. I think it’s a matter of expanding that in a culturally relevant way for each place. I don’t mean putting shinto shrines everywhere in every city, but finding culturally appropriate ways to do that for each of us.”

It takes almost a month, but eventually Brian Mercer, city arborist, let’s me know that, at this time, the city has no plans to remove the tree I asked about. She is safe. For now.

And so here we are under the old willow. I wonder what our city would look like if we listened to its trees. I think about the fires in British Columbia, California and Greece and the work of Athene’s first chief heat officer. Her job is to cool down the city and trees are an inevitable part of her workplan. I am grateful every day for the river and this green oasis of peace almost on my doorstep. And for the old willow who by now, I hope recognizes me in the same way that, I think, that old horse chestnut an ocean away does. I mourn my black poplars and a home that was diminished now that they are gone. Dr. Brown tells me about hundreds of species of willow that grow around the world. She shows me a photograph on her phone of Salix Arctica - a tiny creeping willow that grows above the treeline far in the north. I ask her what can we do to rebuild a little bit of that childish awe and respect for the trees around us. She paused for a second and then she said: “Notice them. Learn a little bit about different kinds of trees that we have here. Look at how they are helping the river bank, look at what other species are growing on them or using them and yeah just appreciate and just acknowledge all that they do in our cities and around our cities to make them a better place for all of us to live in. I feel like Lorax right now. I speak for the trees...”