How we do science

Between the August of 2016 and the winter of 2018, I've been working with a group of researchers and students at Memorial University of Newfoundland's Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR) on a photography project we, for now, call How we do science?

CLEAR is not a typical science lab. Led by Drs. Max Liboiron and Charles Mather, they describe themselves as engaged in "action-oriented research through grassroots environmental monitoring. Civic Laboratory’s techniques are developed in recognition that the process of research, as well as research findings, impact the world. We focus on do-it-yourself, feminist, participatory, and activist methodologies based in local knowledge so research contributes to positive change in the environments in which we work and live." Most of the lab's work is focused on micro plastics in the ocean and the food sources connected to the ocean - fish is the obvious example, but also sea birds and potentially other animals that humans consume as food.

The idea behind the photographs is to engage with daily realities, to quote Stuart Franklin, of how science is done at least in this particular lab. To that end, as a photographer, I am working more closely with the researchers than I normally would in similar documentary projects. One of the ways we collaborate more closely is that the researchers play editorial and curatorial role for the project. For example, after seeing the first batch of photographs, they pointed out that a few of them featured large pieces of plastic on a beach. We decided that they should be removed from the series because they misrepresented the research and perpetuated the stereotypes of what plastics in the ocean look like. CLEAR is researching micro-plastics, which make up vast majority of marine plastics. In fact, 90 percent of marine plastics are under 5mm in size and so not terribly photogenic, but no less troublesome. A comment another researcher left on a sticky note pointed out that "there should be more photographs of downtime and car-pooling." The lack of such photographs is clearly an oversight on my part and probably the result of my own journalistic training that prioritized dynamic photographs of people doing things over a car ride.

Finally, this page will change over time as I make more photographs and as we find better ways to sequence and present this work. I have no idea what that will look like in the end. The current presentation leaves a lot to be desired. For example, showing you tools, data collection, sample analysis, the actual production of academic journal articles, and so on in a neat sequence is misleading. These things can happen in almost any order and even simultaneously. However, this is what we have for now, so keep coming back and see where it ends up.

Data collection

This first sequence of images deals with data collection. The photographs were made at two separate occasions. One set was made in the harbour of Portugal Cove - St. Philips, Newfoundland, during the summer cod food fishery season in August 2016. The researchers worked with local fishers and collected fish guts in order to determine how much marine plastics the fish in this area consumed. The fishers would filet the fish and remove cod cheeks and tongues and pass the fish to the researchers who would measure the carcass, remove the guts, store it and label it in plastic bags.

The second set comes from a beach in Maddox Cove, Newfoundland, where the researchers collected samples of micro plastics in October 2016.

The craft of science

As a part of the editorial process, we pinned 12x18 inch prints around the lab. I encouraged the researchers to use sticky notes and dot stickers to provide feedback and comments on the photographs. There was also an opportunity to collect some feedback from visitors during an open lab event. The comments on this particular series of photographs focused on the craft of science - the physical act of evidence gathering, in this case, the cod fish (Gadus morhua) guts. "[I] like how [it] shows the process (hands in motion)," was one of the comments. Other researchers commented on the monotony of sampling (they collected hundreds of fish guts) and how this part of the process was "very gut-centric."

"Label, label, label"

A researcher who visited the lab during the open lab day pointed out that labeling is where a material sample (fish guts in this case) becomes scientific data. That bit might be debatable, but properly storing and labeling samples is certainly something that the researchers in CLEAR do a lot of. One researcher pointed out the label within square brackets on one of the bags: [hole]. It's a note to the scientist who will dissect the guts to warn them that the sample should be discarded because the guts were punctured during the filleting or the removal from the fish carcass and so could contain plastics introduced during the collection process. The comments on this set of photographs also pointed out that the concentration on the faces of the scientists bagging a set of guts was "on point." In a later conversation during one of the lab meetings young female researchers spoke about media treatment they often receive that minimizes the labour they do and portrays them as squeamish and "girly."

The question of fish

Of all the photographs in this collection so far, two have polarized the researchers. I am including both. The first one, the pile of fish carcasses waiting to have their guts removed, prompted comments that ranged from funny "Uh, guys? Am I supposed to be here?" to "Nice emphasis on the fish as living/dead thing," to outright discomfort with one researcher declaring his dislike of the photograph because the fish seemed to be staring at him. Animal ethics in science are always problematic. CLEAR members explore animal ethics in ways that go beyond the conventional research ethics and look at ethics protocols that recognize feminist, Indigenous and decolonial approaches to animal ethics and care.

A grain of rice in an ocean

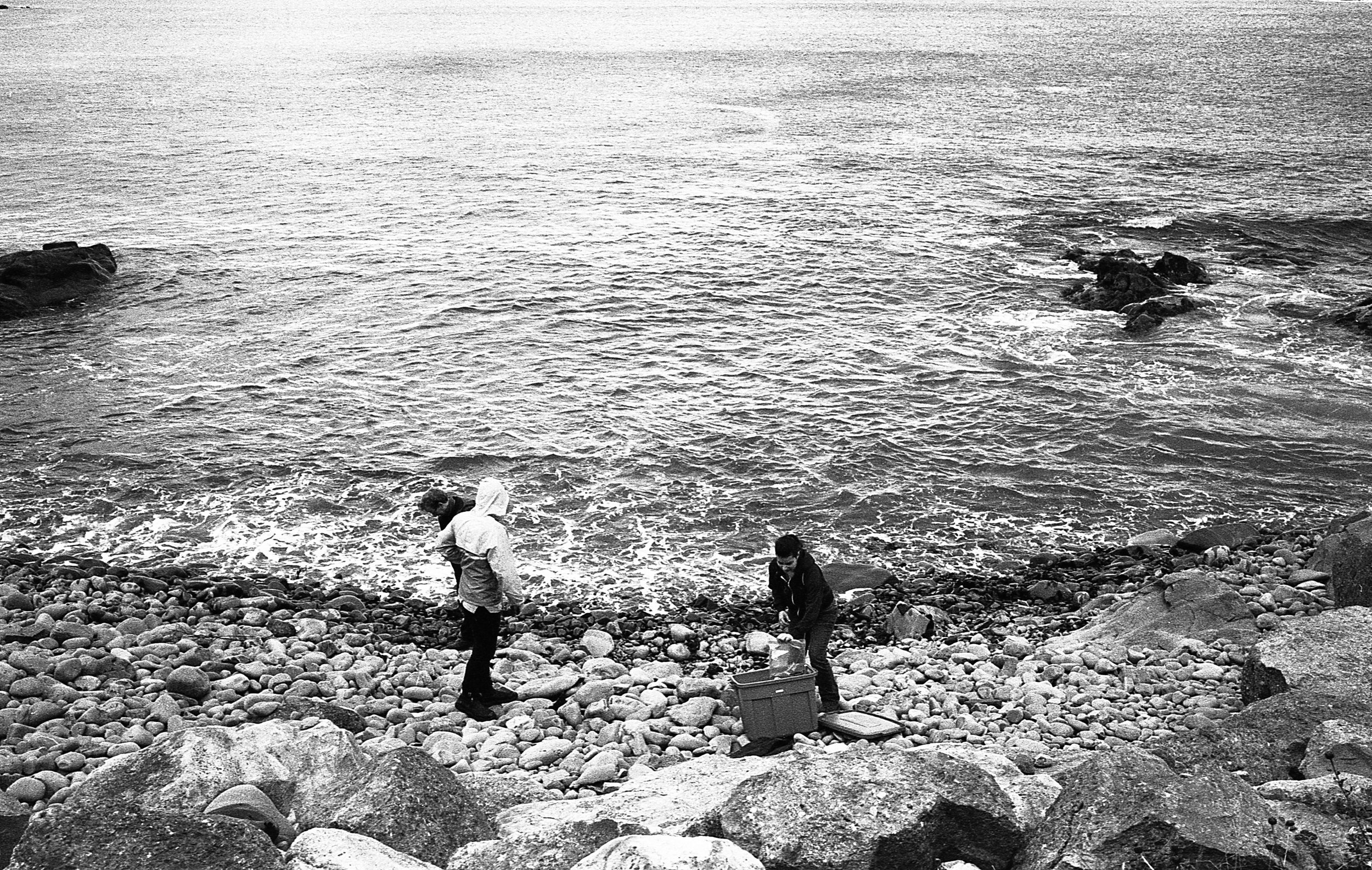

The second photograph that caused a strong reaction among some of the lab members is the one above. It was made in Maddox Cove during a sampling on a local beach. Quite a few researchers liked the contrast between the enormity of the ocean behind the comparatively small scientist figures in the foreground. One researcher, however, found the ocean daunting and threatening. The task of finding plastics that are the size of a grain of rice or smaller in an ocean is indeed a somewhat dispiriting task.

Beach sampling

Looking inside seabird and fish guts for ingested plastics is only one of data collection methods CLEAR uses in their search for micro-plastics. Beach sampling is another method that involves measuring the actual beach and then creating one square meter random sample areas that are then thoroughly searched for micro plastics. In many ways that is a more difficult task on rocky Newfoundland beaches than in many other environments. Tiny pieces of plastic easily fall between the large rocks and the team has to carefully remove that top layer of stones and sift through sandy strata below - a laborious and, in October when these photographs were made, a cold task.

"good 'thinking faces' here"

During the editing process, the researchers were particularly drawn to photographs of "thinking faces." While it may seem trivial- people who do science are expected to have their "thinking faces" on most of the time- it mattered to younger and female researchers that they could see themselves and be seen as serious while they go about their work. The focus on "thinking faces" is less surprising in the context of the researchers' previous comments on how they are sometimes represented in media reports.