River Walks and Where Documentary Project Ideas Come From

A FRIEND OF MINE WHO TEACHES at the local journalism school asks me, every November, to come and speak to his class about documentary photography. He almost never agrees with what I tell his photojournalism students, but, thankfully, he seems to forget that by the time the next November rolls around.

This past year, I did not get to speak to his students who, like the rest of us, are trying to keep their heads above the water during this pandemic. I did, in mid-November, finish a documentary for Atlantic Voice, CBC’s regional show in Atlantic Canada. One of the things I loved about it was that it started as a series of photographs and only later became a radio show.

Here in St. John’s, on the island of Newfoundland, the number of cases of COVID-19 has been relatively low and manageable. The strict self-isolation, contact tracing, and travel restrictions policies, with good compliance have so far kept us safe from a major outbreak.

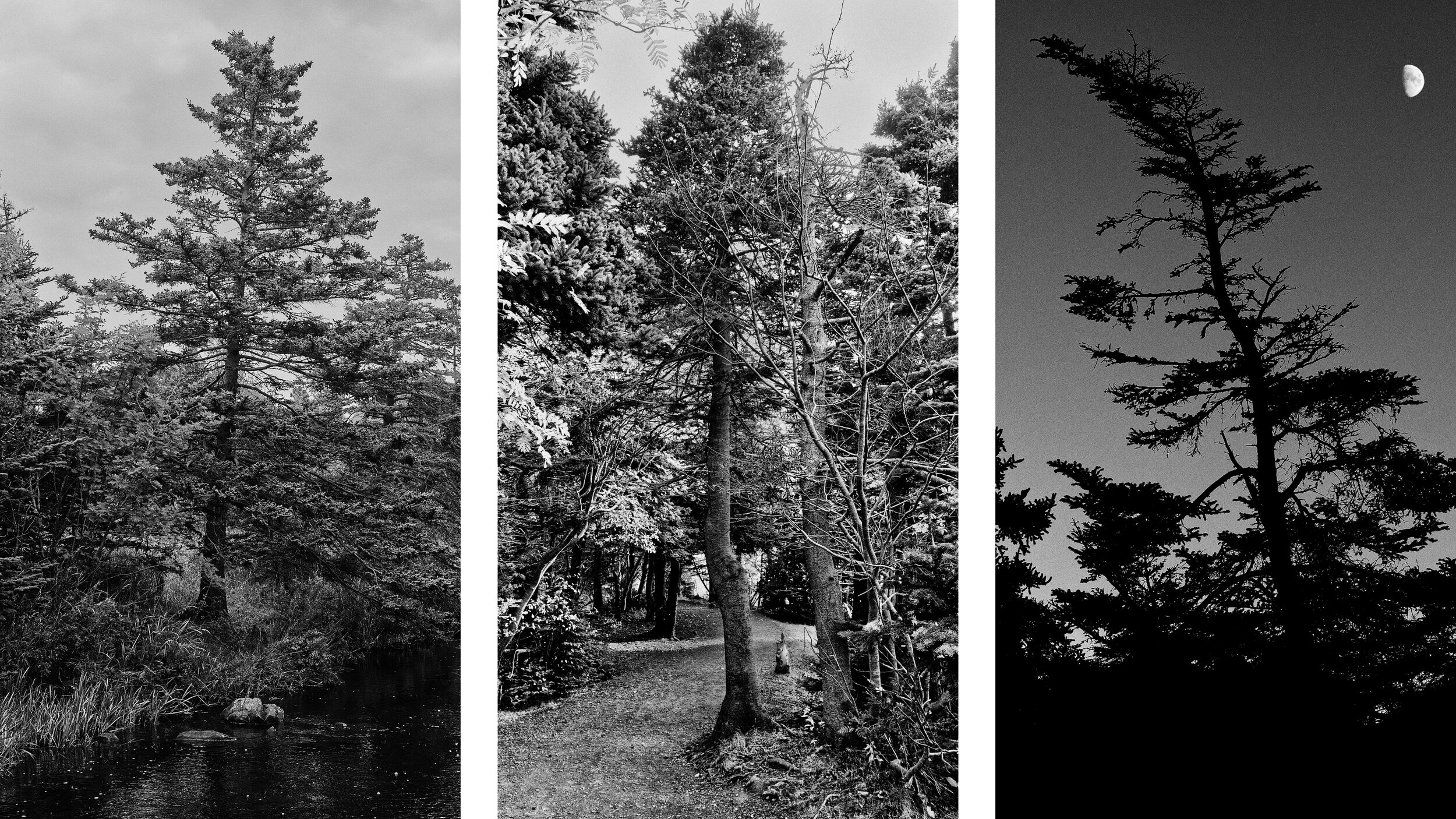

As a way to cope with my severely limited ability to travel, I started walking along the river that runs through some of the oldest residential neighbourhoods in the city. That radio documentary and the photographs you see here are the result of those walks.

Another thing this pandemic was good for is an avalanche of free webinars and video conversations put together by some of the largest photo organizations in the world. The reason I am telling you all this is that one question inevitably gets asked at those webinars and often in those talks I give at the journalism school. “Where do you get an idea for a documentary project?” is a question that always baffles me and I never know how to answer it without sounding condescending.

So here it is. I think that if you have to ask that question, then maybe documentary photography is not your thing. The ideas for documentary projects, photography and audio, and I imagine the writers may feel the same, are everywhere — every person you meet, every book you read, every walk you go on, every movie you watch. There is no magical well of documentary project ideas that other photographers have access to and are keeping secret from you. They don’t just drop down a bucket and pull up a great idea.

Documentary projects are the result of curiosity and an engagement with a broad range of sources. You need to realize how little any of us will ever know and then, when something sparks your curiosity, stay with it. Explore it. Read everything that you reasonably can about the subject. Look at what other people have done with it. Examine why you feel the curiosity and passion about that particular issue.

Developing a documentary project is a complicated process that requires research, interviews, relationship building and understanding of the potential story lines that together make the project meaningful. And you should never confuse a good project idea with a good project. Just because your idea is good, it doesn’t mean that the end product will be. Those are two different things.

For me, project ideas often come from a sustained engagement with a place and people. This can be difficult. We are all pulled in million different direction. For many of us, our work-lives are fractured and largely transactional — typical office work happens in one or two hour blocks with some formulaic communication squeezed in between. That rhythm is not suited to any sort of deep engagement and when you pair that with the distractions of social media, it’s a miracle any of us make anything at all.

The pandemic changed that for me because I was forced to stay put, to explore the same 12 kilometres of that urban river trail over and over again through the changing seasons, in different light, in different moods, and at different times.

Eventually, the trail became so familiar that now I look forward to seeing individual trees along the path the same way I look forward to saying “Good morning!” to my neighbour or mail carrier. More than once, I found myself hurrying to my favourite spots along the banks to see how the rains from the night before changed the river today.

I read about rivers, river riparian zones, invasive species, trees, urban forests, and mycorrhizal networks. I read up on history of the river that eventually led to learnign more about the use of gas in World War I and the development of the first gas masks. The walks and the photographs became the starting point of a far wider exploration of strands in some way connected to the 12 kilometres I was becoming intensely familiar with.

The walks, the photography and the process of gathering facts and observations became almost a meditation. Being a part of the river world on my doorstep made accepting the reality of the pandemic easier recalling to mind the verse in Ursula K. LeGuin’s interpretation of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching:

The things of this world

exist, they are;

you can’t refuse them.

Curiously, the world of photography and literature has been for decades now refusing such narratives of the world that is. Recently, New York Times published Photographing Life as It’s Seen, Not Staged, an opinion piece claiming that documentary photography is having a bit of a comeback moment after it “fell out of favor.” It was a pompous and ridiculous piece of writing, but it did reference Tom Wolfe’s 1989 (truth be told a bit rambling) essay in Harper’s Magazine Stalking the billion-footed beast urging writers, and you can add photographers here, too, to stop thinking small and engage with the world as it is because, indeed, we cannot refuse it. “The answer is not to leave the rude beast […] also known as the life around us,” Wolfe writes, but “to wrestle the beast and bring it to terms.”

And so I always skirt that question of where documentary project ideas come from and instead tell the students to engage with the world around them. Documentary project ideas are found as easily on your doorstep as they are half a world away. And I also tell them that they don’t have to photograph what they know — how boring!— use photography to learn something new and bring us along on that journey. ✖︎

NOTES:

*I also tell my friend’s students that if they want to be better photographers they need to read better books so I leave them with a list of books I am sure they never look at again. Lately, I have been posting some of them on my Instagram account with a #booklist4pjstudents.